Most people think pharmacies make big money off every prescription they fill. But if you’ve ever worked behind the counter or owned a small pharmacy, you know the truth: generics are the only thing keeping many of them afloat. And even then, it’s a tight squeeze.

Here’s the paradox: generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only account for about 25% of total drug spending. Brand-name drugs? They’re just 10% of prescriptions-but they soak up 75% of the cash. So how do pharmacies stay in business? The answer lies in the margins-and they’re wildly different between generics and brands.

Generics Bring the Profits, Brands Bring the Costs

When a pharmacy dispenses a brand-name drug like Humira or Ozempic, the list price might be $1,200 a month. But the pharmacy’s gross margin? Just 3.5%. That’s $42 on a $1,200 script. After paying rent, staff, utilities, and insurance claims, the net profit might be less than $5.

Now take a generic version of the same drug-say, a 30-day supply of metformin that costs $4 at the manufacturer. The pharmacy buys it for $1.50 and sells it for $10. Gross margin? 42.7%. That’s $8.50 profit on a $10 script. Multiply that by 50 prescriptions a day, and suddenly you’re talking real money.

It’s not magic. It’s math. Generics are cheap to make, and pharmacies get to mark them up significantly because the system allows it. But here’s the catch: those high gross margins don’t always turn into net profits.

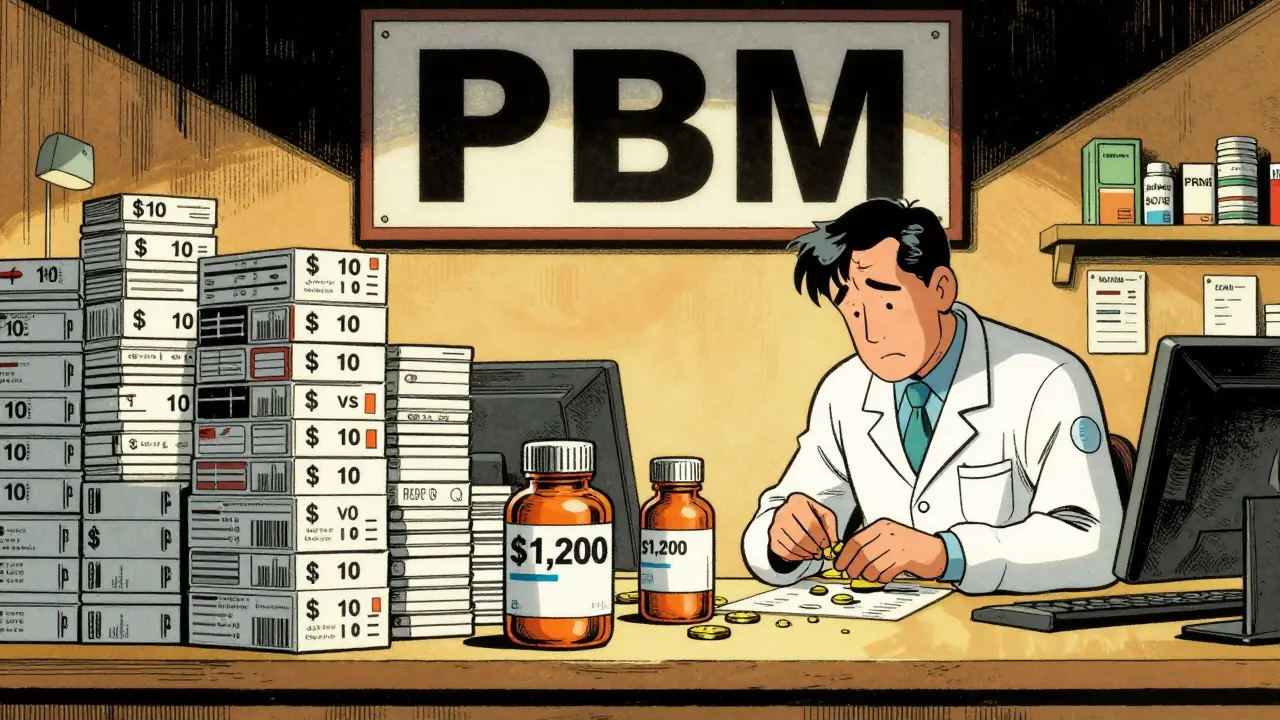

How PBMs Eat Into Your Profit

Pharmacies don’t get paid directly by patients or insurers. They get paid by pharmacy benefit managers-PBMs like CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx. These are the middlemen who negotiate prices between drugmakers and insurers. And they’ve built a system that works against independent pharmacies.

PBMs use something called “spread pricing.” They tell the insurer they’re paying $8 for a generic drug. But they only reimburse the pharmacy $5. The $3 difference? That’s their profit. And they don’t have to tell you what they’re charging the insurer. You just get paid what they say you’re getting paid.

Then there’s “clawbacks.” Imagine you fill a prescription for a $10 generic. The PBM reimburses you $10. A week later, they find out the actual cost was $7. They demand you pay back $3. No warning. No notice. Just a chargeback on your next payment. Independent pharmacies lose millions this way every year.

A 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of independent pharmacy owners listed declining generic reimbursement as their #1 business threat. Five years ago, gross margins on generics were around 24%. Now they’re down to 19.8%. Overhead? Up 35%.

Why Some Generics Cost More Than Brands

You’d think more competition means lower prices. And for a while, it did. But over the last decade, the generic drug market has consolidated. In 2015, the top five generic manufacturers controlled 32% of the market. By 2023, that jumped to 45%.

What happens when only one company makes a generic version of a drug? Competition disappears. And prices spike. In some cases, the single-source generic now costs more than the brand-name version.

One Ohio pharmacist told Pharmacy Times he was paying $120 for a generic version of a drug that still sold for $90 as a brand. Why? Because no other manufacturer could get FDA approval fast enough. The brand had expired, but the generic hadn’t caught up. So patients paid more for the generic.

The FDA approved over 2,400 new generics between 2018 and 2020-saving an estimated $161 billion. But that doesn’t help pharmacies if the market is controlled by just a few players who can set prices without fear of competition.

Mail-Order Pharmacies and the Hidden Margin Gap

While your local pharmacy struggles, mail-order pharmacies are thriving. Why? Because they’ve cracked the code.

For a generic drug, mail-order pharmacies make more than four times the margin of a small retail pharmacy. For brand drugs? The difference is even wilder-mail-order pharmacies make over 35 times the margin. In some cases, they’re making 1,000 times more profit on a generic than a local store.

How? Scale. They fill tens of thousands of prescriptions a day. They negotiate directly with manufacturers. They don’t rely on PBMs the same way. And they often operate without the overhead of a storefront.

Meanwhile, independent pharmacies-40% of all U.S. pharmacies-are filling just 11% of prescriptions. Between 2018 and 2023, over 3,000 closed. That’s not just bad news for owners. It’s bad news for communities that lose their only local pharmacy.

How Successful Pharmacies Are Surviving

Some pharmacies aren’t waiting for the system to fix itself. They’re changing the game.

- Medication Therapy Management (MTM): Instead of just filling scripts, pharmacists now offer consultations on drug interactions, side effects, and adherence. Medicare pays for this service. Some pharmacies earn $50-$100 per patient per visit.

- Specialty Pharmacy Services: Drugs for cancer, MS, or rare diseases pay better. These aren’t $10 generics-they’re $10,000-a-month treatments with built-in reimbursement structures.

- Direct-to-Consumer Pricing: Pharmacies like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company charge $20 for a generic plus a $3 dispensing fee. No PBM. No spread pricing. Just transparency. They’ve processed over a million prescriptions since 2023.

- Employer Direct Contracts: Some pharmacies skip PBMs entirely and contract directly with employers. They get paid a flat fee per script, no clawbacks, no surprises.

Pharmacies using these strategies report net margins of 4-6%. That’s not luxury, but it’s survivable.

What’s Coming Next

The Inflation Reduction Act, starting in 2026, will let Medicare negotiate prices for 10 brand-name drugs a year. That could lower overall drug spending-but it won’t fix the generic margin problem.

Meanwhile, states like California, Texas, and Illinois have passed laws forcing PBMs to disclose how much they’re charging insurers versus paying pharmacies. The FTC is investigating price-fixing in the generic market. And Amazon Pharmacy now shows exact drug costs upfront-$5 for generics, no mystery.

But here’s the reality: if nothing changes, Goldman Sachs predicts 20-25% more independent pharmacies will close by 2027. The system is rigged to favor big players with scale, not local owners trying to make rent.

Generics were supposed to save money. And they did-for insurers and patients. But the pharmacies that dispense them? They’re the ones paying the price.

Why This Matters Beyond the Counter

This isn’t just about pharmacy profits. It’s about access. When a small-town pharmacy closes, residents drive 30 miles for insulin. Seniors skip doses because they can’t afford the co-pay. Pharmacists burn out from juggling impossible reimbursement rules.

The solution isn’t to stop generics. It’s to fix the system that’s squeezing the people who deliver them. Transparency. Fair reimbursement. Real competition. Without those, the pharmacy on the corner won’t just disappear-it’ll be the first casualty of a broken drug pricing system.

8 Comments

Let’s cut through the noise: the PBM model is a classic rent-seeking oligopoly disguised as healthcare logistics. Spread pricing, clawbacks, and opaque formulary tiering are structural extraction mechanisms-essentially, PBMs act as private tax collectors on the back end of the generic supply chain. The FTC’s investigation is long overdue, but unless you break up the vertical integration between PBMs, insurers, and mail-order pharmacies, you’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. Independent pharmacies aren’t failing because of poor management-they’re being systematically starved by a consolidated, anti-competitive infrastructure.

It’s fascinating how the economics of generics have inverted over the last decade. Back in the early 2000s, we thought generics would democratize access and empower small pharmacies. Instead, we got consolidation, regulatory capture, and a race to the bottom on reimbursement. The irony? The very drugs meant to reduce costs have become the backbone of a system that crushes the people who distribute them. Mail-order giants thrive because they’ve outsourced the human element-no counseling, no community trust, just volume and automation. Meanwhile, the local pharmacist who remembers your kid’s name and catches your dangerous interaction? They’re getting paid less than minimum wage per script after clawbacks. We’re not just losing pharmacies-we’re losing the human layer of care.

Wow, this is so true. I work in a small clinic and see how hard pharmacists work just to keep things running. Sometimes the generic costs more than brand and no one knows why. It’s just confusing for everyone. Hope things get better soon.

There’s a quiet revolution happening in pharmacy-away from the PBM-controlled chaos. Pharmacies like Cost Plus Drug Co. are basically saying, ‘We’re not playing your rigged game.’ And people are responding. Transparency isn’t just ethical-it’s disruptive. Imagine a world where you walk in and see the real cost of your metformin, not some PBM-angled number that’s been twisted through three layers of middlemen. It’s not just about profit margins-it’s about restoring dignity to the act of dispensing medicine. Pharmacists aren’t just clerks; they’re the last line of defense against medication errors, cost traps, and misinformation. When we treat them like cogs, we all pay the price-in health, in trust, in lives.

I’ve seen this up close. My grandma’s pharmacy closed last year after 42 years. She cried because the new pharmacist didn’t know her meds or her dog’s name. This isn’t just business-it’s community erosion. We need to stop pretending this is just about numbers. Real people are losing access. Real pharmacists are burning out. Real seniors are skipping doses because the ‘cheap’ generic got clawed back. We can fix this if we stop letting the middlemen write the rules. Support local. Demand transparency. Vote with your wallet.

EVERYTHING YOU SAID IS TRUE BUT YOU’RE MISSING THE BIGGER PICTURE 🤫... PBMs are just the tip of the iceberg. The real puppet masters? Big Pharma + Wall Street hedge funds that own 78% of the top 5 generic manufacturers. It’s a coordinated oligopoly disguised as competition. The FDA approves ‘new’ generics but only after the incumbent buys out the competitor. The FDA is basically on payroll. And don’t get me started on how the Inflation Reduction Act is a Trojan horse-Medicare negotiating prices? Nah. They’re just shifting the burden from insurers to pharmacies. You think they’ll raise reimbursement? HA. They’ll just cut it further. This is a controlled demolition of community pharmacies to make way for Amazon + CVS + Optum. Wake up. 🚨💸

So let me get this straight: we have a system where a $1.50 pill sells for $10, but the pharmacy gets $5, then gets clawed back $3, while some guy in a Connecticut office makes $3 profit… and you’re surprised pharmacies are dying?? 😭 I mean, come ON. This isn’t capitalism-it’s a parody of capitalism. Someone needs to start a podcast called ‘PBM: The Real Villains of Healthcare’ and just post screenshots of their reimbursement statements. I’d binge it. Also, Mark Cuban is a hero. Send him cookies. 🍪

Pathetic. You think this is a crisis? Try being a pharmacist in 2024. You’re a glorified order filler for a broken system. The fact that you’re even surprised generics are profitable? That’s the problem. You’re not thinking like a real businessperson-you’re thinking like a charity case. The solution? Stop whining. Raise prices. Drop Medicaid. Go specialty. Or just close. The market doesn’t care about your feelings. If you can’t adapt, you don’t deserve to exist. 🤷♂️