When you pick up a prescription for a combination drug-like a pill that contains two or three medicines in one-you might assume your pharmacist can swap it out for a cheaper version. But that’s not always legal. And even when it’s allowed, it can be risky. Combination drugs are becoming more common, especially for chronic conditions like HIV, heart disease, and diabetes. But the rules around substituting them haven’t kept up. Pharmacists are caught in the middle: they want to save patients money, but they’re also afraid of breaking the law or harming someone.

What Exactly Is a Combination Drug?

A combination drug is a single dosage form-like a tablet or capsule-that contains two or more active ingredients. These aren’t just random mixes. They’re carefully designed to work together. For example, ATRIPLA combines efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir into one pill for HIV treatment. Another example is the cancer drug combination of pembrolizumab and lenvatinib, approved by the FDA in 2021. These aren’t just convenience products. They’re meant to improve adherence, reduce side effects, and simplify treatment for patients juggling multiple medications.

But here’s the catch: these drugs are treated differently under the law than single-ingredient pills. The FDA defines combination products as those that include two or more regulated components-drugs, biologics, or devices-packaged together. That means even if one part of the combination is generic, the whole product can’t be swapped out like a regular generic. Substituting a combination drug isn’t like swapping one brand of ibuprofen for another. It’s more like swapping a car engine with a whole different model. The parts might look similar, but the system they’re part of isn’t interchangeable.

Why Existing Substitution Laws Don’t Work

Most U.S. states have laws that let pharmacists substitute generic versions of prescribed drugs-so long as they’re pharmaceutically equivalent. That means same active ingredient, same strength, same form. Simple enough. But when a prescription calls for a combination drug, things get messy.

Let’s say your doctor prescribes a pill with two blood pressure medications: amlodipine and lisinopril. Your pharmacist might have a generic version of that exact combo. But what if they only have a generic of amlodipine and a separate generic of lisinopril? Can they give you those two pills instead? Legally, no. That’s not substitution-that’s compounding. And compounding requires special licensing and oversight.

Worse, some states allow pharmacists to switch one drug for another with a similar effect-called therapeutic substitution. But that’s only allowed for single-agent drugs. You can’t swap a beta-blocker for an ACE inhibitor without the doctor’s okay. Now imagine that same rule applies to a combination pill. If your doctor prescribed a combo with three drugs, and your pharmacist wants to swap it for a different combo with two of the same drugs plus a new one, that’s not just substitution-it’s changing your treatment plan. And in most states, only a prescriber can do that.

A 2022 survey by the National Community Pharmacists Association found that 68% of pharmacists ran into substitution dilemmas with combination drugs at least once a month. Nearly half of them refused to substitute because they weren’t sure if it was legal. That’s not a sign of poor training-it’s a sign that the rules are broken.

The Legal Gray Areas

The law varies wildly from state to state. In some places, pharmacists can’t substitute any combination product without explicit permission from the prescriber. In others, they can swap identical combinations-but not different ones. The Alberta College of Pharmacy makes it clear: substituting a single drug with a combination product is considered starting new therapy. That requires prescribing authority, which most pharmacists don’t have.

Even when two combination products contain the same active ingredients, they might not be interchangeable. Take two pills that both contain metformin and sitagliptin. One might be an immediate-release version. The other might be extended-release. Even though the ingredients are the same, the way they’re released into your body is different. That can change how well the drug works-and how many side effects you get.

And then there’s the issue of modified-release formulations. Some combination drugs use special coatings or time-release tech to control how the ingredients are absorbed. If you swap that for a generic version without the same release mechanism, you could end up with too much drug at once-or not enough. That’s not just a technicality. It’s a safety risk.

In 2022, the 9th Circuit Court ruled in Smith v. CVS Caremark that pharmacists can’t substitute a combination product that includes active ingredients not listed on the original prescription. That case set a precedent: if the combo has extra ingredients, it’s not a substitute-it’s a new drug.

Practical Problems for Pharmacists

Pharmacists aren’t just following rules-they’re trying to keep patients safe. But they’re also under pressure to cut costs. Insurance companies push for cheaper alternatives. Patients ask why their copay went up. And with over 90% of prescriptions filled with generics, substitution is expected.

But with combination drugs, the tools don’t exist. Most pharmacy software doesn’t flag whether a substitution is legal for a combo product. Drug databases don’t clearly label which combinations are interchangeable. And state laws aren’t synced. A pharmacist in Texas might be allowed to swap one combo, but the same swap in California could be illegal. If a patient moves or travels, that confusion becomes a safety hazard.

And it’s not just about pills. Some combination products include devices-like insulin pens that combine a drug with a delivery system. Swapping those isn’t even possible without changing the device. But most substitution laws were written before these kinds of products existed.

The American Pharmacists Association says prescribing by adaptation (changing a prescription) is only allowed for new prescriptions. At refill time, switching a combination drug is considered managing ongoing therapy-and that requires prescribing authority. So even if the pharmacist knows a better combo exists, they can’t legally make the switch unless the doctor approves it.

Cost Savings vs. Patient Safety

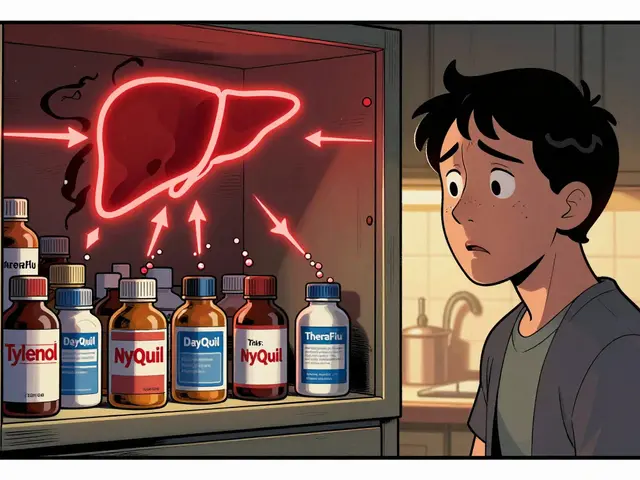

There’s no denying the financial upside. Combination drugs can be expensive. The global market hit $184.3 billion in 2022. But generic single drugs make up 90% of prescriptions while costing only 23% of total drug spending. That’s why payers want to push substitution.

Dr. Jane Chen from ICER estimates that expanding substitution for combination drugs could cut medication costs by 15-25% for chronic conditions. The UK’s NHS saved £280 million annually after implementing strict substitution protocols for cardiovascular combos. That’s real money.

But the risks are real too. The American Heart Association warns that inappropriate substitution in cardiovascular combos could lead to adverse events in up to 8% of patients-especially older adults with multiple health issues. A tiny change in dosage timing or drug interaction could trigger a heart attack, stroke, or kidney damage.

The European Medicines Agency is blunt: therapeutic substitution of complex combination products without physician oversight is dangerous. That’s especially true for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is very small.

What’s Changing?

Things are starting to shift. In September 2022, the FDA released draft guidance on how to prove therapeutic equivalence for fixed-dose combinations. That’s a big deal. It’s the first time they’ve laid out a clear path for evaluating whether two combo drugs can be swapped safely.

In March 2023, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy proposed new model legislation that would create a tiered system. Simple combos-like two well-known drugs in a stable formulation-could be eligible for pharmacist substitution. Complex combos-those with new mechanisms, narrow therapeutic windows, or special delivery systems-would require prescriber approval.

The European Commission has also flagged harmonizing substitution rules for combination medicines as a top priority. That means countries might start aligning their laws, which could make cross-border care easier.

But until these changes are adopted and enforced, pharmacists are flying blind. And patients are the ones paying the price-in higher costs, confusion, or worse, health risks.

What Patients Should Do

If you’re on a combination drug, don’t assume your pharmacist can swap it. Ask these questions:

- Is this combo drug interchangeable with another product?

- Will switching affect how the medicine works in my body?

- Do I need to talk to my doctor before any substitution?

Keep a list of all your medications-including dosages and brand/generic names. Bring it to every appointment. If your pharmacist suggests a change, ask them to explain why it’s safe and legal. If they can’t, insist on talking to your prescriber.

Don’t let cost pressure override safety. A cheaper pill isn’t better if it doesn’t work-or if it makes you sick.

What Needs to Happen Next

Fixing this isn’t about more rules-it’s about smarter rules. We need:

- Federal guidance that standardizes how combination drugs are evaluated for substitution

- Pharmacy software updates that flag legal substitution options in real time

- Clear labeling on combination products that says whether they’re interchangeable

- Training for pharmacists on the legal and clinical boundaries of substitution

Combination drugs are the future of chronic disease care. But our laws are stuck in the past. Until we update them, we’re risking patient safety just to save a few dollars.

14 Comments

This is why America is falling apart 🤦♀️ We can't even swap pills without a 12-page legal brief! 🇺🇸💥 When I was in India last year, pharmacists just gave me what worked. No paperwork, no drama. We need to stop overthinking and start saving lives!

Ive been saying this for years the pharmaceutical industry is a cartel and the government is in on it they make you take 5 pills when one would do and then charge you 5x the price and now theyre even stopping pharmacists from helping you because theyre scared of lawsuits and dont care about your health just their profits

Man this is so real. Back home in India we just get the combo pills and if it works you keep it. No one cares if its exactly the same brand. If the doctor says it's fine, you take it. Why are we making this so complicated?

America thinks its so smart but we cant even fix a simple pharmacy rule. You want cheaper meds? Let pharmacists do their job. Stop the red tape. This is why people skip doses. This is why people die.

Yo this is wild. I work in med logistics and we see this daily. Some combos are totally swappable like metformin+sitagliptin - same active ingredients, same release profile. But the software doesn't flag it. The FDA hasn't labeled them. So pharmacists play it safe and say no. Meanwhile patients pay $300 for a pill that could be $12. It's not incompetence - it's systemic failure.

Ah yes, the classic American healthcare paradox: we have the most advanced pharmaceutical science on earth, yet we still can't figure out how to let a pharmacist swap a pill. How do we have Mars rovers but not interoperable drug databases? Truly, the pinnacle of human achievement.

Let’s be real - pharmacists aren’t doctors. They’re not trained to reconfigure complex regimens. You want cost savings? Fine. But don’t pretend it’s safe to let someone who counts pills for a living decide your heart meds. The system’s broken, but the answer isn’t to hand out prescribing power like candy. It’s to fix the damn formulary systems.

In India, we have a phrase: "Doctor ka bhaav, pharmacist ka kamaal" - the doctor's intention, the pharmacist's skill. We trust the pharmacist to know what's best. But here? You need a lawyer to fill a prescription. And now you're telling me we're going to fix this with... software updates? We need cultural change, not just code.

It's all about control. The system doesn't want you to be empowered. It wants you dependent. Pills are not just medicine - they're a tool of obedience. When you can't swap them, you're forced to keep coming back. To the doctor. To the pharmacy. To the endless cycle of bills. This isn't about safety. It's about power.

I can't believe people are still arguing about this. It's simple: if it's not the exact same pill, don't give it. People die from mixing meds. Why are you risking someone's life to save $20? This isn't a debate - it's negligence.

I'm a clinical pharmacist and I've seen the data. In 85% of cases where patients were switched from branded combos to generic singles, adherence improved and costs dropped. But the legal risk? It's terrifying. We need a federal tiered system - like the NABP proposed. Simple combos = pharmacist discretion. Complex = prescriber approval. It's not rocket science.

So let me get this straight - we have AI that can predict cancer from a scan but we can't build a pharmacy system that says "this combo is interchangeable"? 😅 I mean... we literally have robots that fold laundry. Can't we have a button that says "safe to swap"? This is 2025, not 1998.

I've worked in rural pharmacies for 12 years. Patients come in crying because their copay jumped from $5 to $85. We have the generics. We know they work. But the law says no. So we give them a coupon for a free visit to the clinic - and pray they can afford the gas to get there. This isn't policy. It's cruelty disguised as caution.

You think this is bad? Try being on a combo drug and having your insurance deny the refill because "it's not on formulary" - even though the pharmacist says it's interchangeable. Then you have to wait 3 days for a doctor to approve it. Meanwhile you're dizzy and nauseous. 💊😭 This system is designed to make you suffer before you get help.