When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. That’s the whole point of bioequivalence - it’s the guarantee that the active ingredient gets into your bloodstream the same way, at the same speed, and in the same amount. But here’s the problem most people don’t know about: batch variability can make that guarantee unreliable.

What Is Batch Variability, and Why Does It Matter?

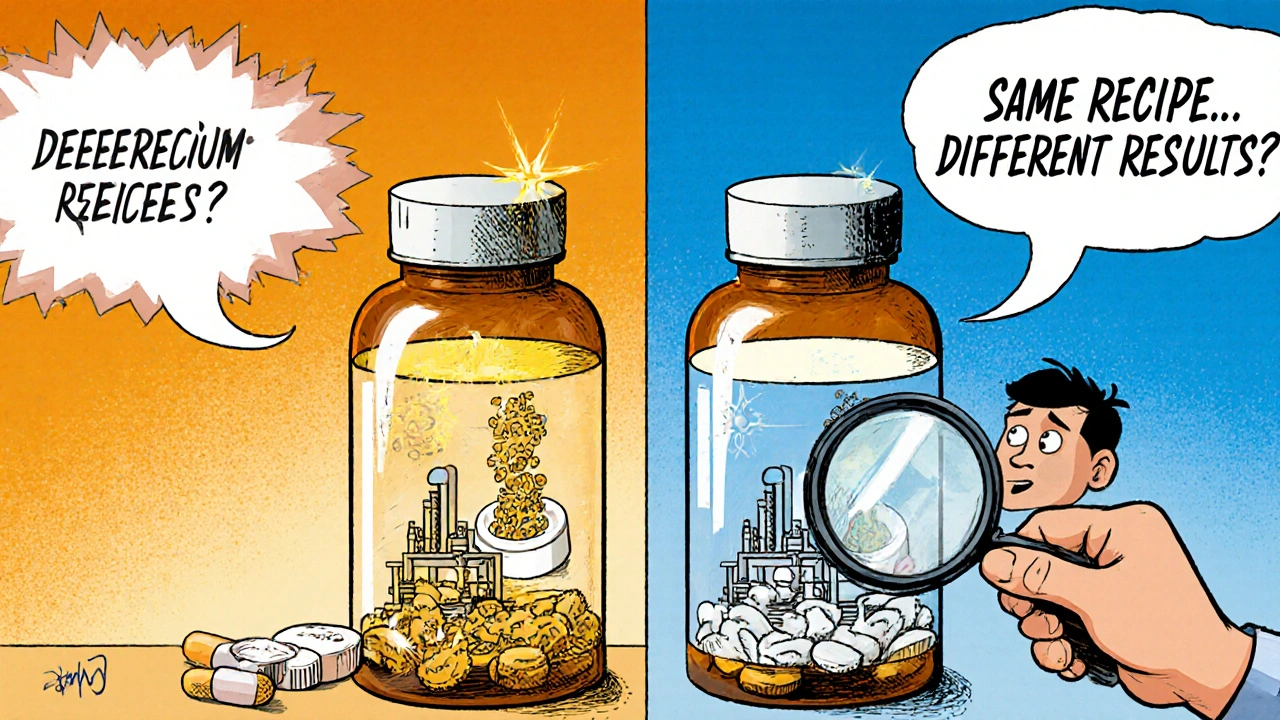

Batch variability means that even two pills made from the same formula, but from different production runs, can behave differently in your body. This isn’t about poor quality control. It’s about the natural, unavoidable differences that happen during manufacturing - slight changes in mixing, drying, compression, or coating. These tiny differences add up. A 2016 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that between-batch differences accounted for 40% to 70% of the total error in bioequivalence studies. That’s not noise. That’s a massive source of uncertainty. Think of it like baking cookies. You follow the same recipe every time, but one batch comes out chewier, another crispier. Now imagine those cookies are medicine. If one batch delivers 10% more drug than another, and you’re testing a generic against just one batch of the brand-name product, you might wrongly say they’re equivalent - or worse, reject a perfectly good generic because it was tested against an unusually high or low batch of the reference.The 80-125% Rule: The Standard That Doesn’t Account for Reality

For over 30 years, regulators like the FDA and EMA have used the same rule: if the ratio of the average blood levels (AUC and Cmax) between the generic and brand-name drug falls between 80% and 125%, they’re considered bioequivalent. It’s simple. It’s been used globally. And it’s outdated. This rule treats every drug like it’s the same - whether it’s a simple tablet or a complex inhaler with hundreds of moving parts. But drugs like nasal sprays, inhalers, or topical gels are far more sensitive to manufacturing changes. A small shift in particle size or spray pattern can change how much drug actually reaches your lungs or skin. The 80-125% range doesn’t adjust for that. It doesn’t ask: How much does the brand-name product itself vary between batches? The result? Studies show that when batch variability is high, the standard test can give false results. A generic might be declared bioequivalent even if it’s not - or rejected even if it’s perfectly safe and effective. That’s not just a statistical glitch. It’s a risk to patient care.Why Single-Batch Testing Isn’t Enough Anymore

Right now, most bioequivalence studies test just one batch of the generic drug against one batch of the brand-name drug. That’s it. But if the brand-name product’s own batches vary by 15%, and you pick a high batch for testing, your generic might look like it’s delivering less - even if it’s actually consistent with the brand’s average. A 2016 study showed that this approach can lead to error rates higher than the accepted 5% threshold. In other words, one in 20 bioequivalence studies might be wrong - not because of bad science, but because of bad design. Regulators are starting to catch on. The FDA’s 2022 guidance on nasal sprays now asks for data from at least three production-scale batches of both the test and reference products. The EMA’s 2023 workshop on complex generics listed “inadequate consideration of batch variability” as one of the top three challenges in generic drug approval. And industry is responding: 78% of major generic manufacturers now test multiple batches, up from just 32% in 2018.

The New Approach: Between-Batch Bioequivalence (BBE)

There’s a better way. It’s called Between-Batch Bioequivalence, or BBE. Instead of comparing the generic to a single batch of the brand, BBE compares it to the brand’s typical range of variation. Here’s how it works: First, you test multiple batches of the brand-name drug - say, six - and measure how much they vary from each other. You calculate the standard deviation of those batches. Then, you test your generic against the average of those batches. The generic passes if its average response is within two times that standard deviation. That’s it. This method doesn’t require more patients. It doesn’t make studies more expensive. It just makes them smarter. A 2020 study in Pharmaceutical Statistics showed that when you test six reference batches, the chance of correctly identifying a truly equivalent product jumps from 65% to over 85%. BBE is already being used for some products. The FDA’s guidance on budesonide nasal spray recommends this kind of variance decomposition. But it’s still not the rule. It’s the exception.What’s Changing in 2025?

The shift is coming fast. In June 2023, the FDA released a draft guidance titled Consideration of Batch-to-Batch Variability in Bioequivalence Studies. The final version is expected in mid-2024. The EMA is also reviewing updates to its 2010 guideline, with public consultation already underway. By 2025, it’s likely that for any complex generic - inhalers, injectables, nasal sprays, or even extended-release tablets - regulators will require:- At least three batches of the reference product

- At least two batches of the generic

- Statistical models that separate within-subject variability from between-batch variability

- Full characterization of batch consistency, including dissolution profiles and particle size distributions

What This Means for Patients

You might not see any change on the pill bottle. But behind the scenes, the system is getting tougher - and more reliable. If you’re taking a generic for a critical condition - like epilepsy, heart disease, or thyroid disorders - you now have more confidence that the version you get today will behave like the one you got last month. The days of unpredictable effects from “different batches” are fading. For patients who’ve experienced unexpected side effects or loss of effectiveness after switching generics, this change could explain why. It wasn’t always your body. Sometimes, it was the batch.What’s Still Missing

Even with BBE and multi-batch testing, gaps remain. The current rules still don’t fully account for how variability affects different populations - children, elderly, or people with liver or kidney disease. And while BBE works well for drugs with high variability, it’s not yet standardized for all product types. Also, many generic manufacturers still test only one batch to save time and money. Until regulators make multi-batch testing mandatory, there will be inconsistencies. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is working on new guidelines (Q13) for continuous manufacturing - a shift away from batch production altogether. If that takes off, batch variability could become a thing of the past.Bottom Line: The Standard Is Evolving - And You Should Know Why

Bioequivalence isn’t just about matching numbers. It’s about matching real-world performance. The old 80-125% rule was a good start. But as drug delivery gets more complex, we need better tools. The future of generic drugs isn’t about cheaper pills. It’s about smarter science. And if you’re relying on generics - whether for cost, access, or both - you deserve to know that the system is finally catching up to the science.What’s next? Expect to see more detailed information on drug labels - not just the name and dose, but the batch consistency data behind them. Regulators are moving toward transparency. And that’s a win for everyone.

14 Comments

So let me get this straight - we’re telling patients to trust that their generic meds are identical, but the system literally tests ONE batch against ONE batch? That’s like judging two cars by driving one from each factory once and calling it a day. Wild.

And the cookie analogy? Chef’s kiss. I just pictured my grandma’s oatmeal cookies - one batch chewy, one batch crispy - and now I’m terrified of my blood pressure pill.

This is actually really fascinating. I never thought about how manufacturing differences could affect medicine like this. It makes sense - even small changes in how something is pressed or coated can change how it dissolves.

It’s kind of beautiful that science is finally catching up to how messy real-world production really is. Glad to see regulators are starting to demand better data.

The 80-125 rule was a bandaid for a broken system. Now we’re finally stitching the wound properly. No more pretending that all drugs are the same. Biology doesn’t care about convenience. Neither should regulators

Big picture: the current BE paradigm is fundamentally flawed because it conflates within-subject variability with between-batch variability. The 2016 study you cited showed that between-batch variance accounted for 40–70% of total error - that’s not noise, that’s systemic bias.

BBE isn’t just a tweak - it’s a paradigm shift toward variance decomposition. We’re moving from point estimates to distributional equivalence. The FDA’s 2022 nasal spray guidance was the first domino. Q13 will be the avalanche.

Also, dissolution profiling and particle size distribution are non-negotiable for complex generics. If you’re not measuring CQAs, you’re just guessing.

Let me guess - this is all just a corporate ploy. Big Pharma wants to kill generics so they can keep charging $500 for a pill that costs 2 cents to make.

They’re inventing ‘batch variability’ so they can make you pay more for ‘premium generics’ that are just the same old stuff with a fancy label.

And don’t tell me about ‘FDA guidance’ - they’re bought and paid for. I’ve seen the documents. The same people who approved OxyContin are writing these ‘new rules.’

They want you to think it’s science. It’s not. It’s profit.

Check the FDA’s revolving door. 12 former pharma execs in the last 5 years. Coincidence? I think not.

Okay, so... you're saying that sometimes, your generic meds might not work the same because the batch you got was made on a Tuesday instead of a Thursday? And we're just supposed to trust that this is being fixed? I mean, I'm already on 7 meds. Do I really need to start keeping a log of which batch I got? I'm tired. Just fix it already.

Wow. A whole article about pills? How dull. I mean, I get it - you’re trying to sound smart. But this is just a fancy way of saying ‘sometimes generics are weird.’

Also, I’ve been taking my thyroid med for 12 years and I know exactly which brand I need - and no, I’m not switching to some ‘BBE-approved’ version just because some guy in a lab coat says so.

Real talk: if you’re not on the exact same pill you’ve always taken, you’re basically gambling with your life. And I’m not playing.

The system's broken but not because of batches. It's broken because we treat medicine like soda. You don't need six batches to test a pill. You need better people. And less bureaucracy

This is the kind of deep, thoughtful stuff we need more of.

It’s scary to think that someone’s epilepsy control could hinge on whether their pill was made in batch #3 or batch #7. But it’s also hopeful - because people are finally listening.

To the patients who’ve felt dismissed when they said, ‘This one doesn’t feel right’ - you weren’t crazy. It wasn’t you. It was the system.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with my support group. We’ve all had that moment - the one where the meds just… don’t work. Now we have words for it.

Bro, this is gold. 🙌

India’s generic industry is massive - we make 60% of the world’s generic pills. But honestly? Most of us still test one batch because it’s cheaper and faster. This BBE thing? It’s not just good science - it’s good business.

Imagine if a patient in Kenya gets a bad batch and blames ‘Indian generics’? That hurts everyone. Multi-batch testing isn’t a cost - it’s a reputation shield.

Also, particle size? Dissolution profile? Yeah, we’ve been doing this for years in advanced labs. Just need the regulators to catch up.

Respect to the FDA for leading this. Time to globalize the standard.

Wait - you’re saying the FDA doesn’t even test multiple batches? That’s insane. And you’re just… accepting this? You’re telling me people are getting inconsistent doses and we’re just shrugging?

Someone should sue. Like, class-action. Every person who had a seizure, or a stroke, or a panic attack after switching generics? They should get paid. This isn’t science - it’s negligence.

And why isn’t this on the news? Why is no one talking about this?!

While I appreciate the technical depth of this analysis, I must emphasize that the proposed BBE framework lacks sufficient clinical validation. The statistical models referenced are derived from controlled, homogenous populations - yet real-world patients exhibit wide pharmacokinetic heterogeneity due to age, comorbidities, polypharmacy, and genetic polymorphisms.

Without prospective, longitudinal, multi-center trials accounting for these variables, any regulatory shift toward BBE is premature - and potentially dangerous. The FDA’s draft guidance reads more like a marketing brochure than a scientific consensus.

Until we can prove that BBE reduces adverse events - not just statistical variance - we are replacing one form of uncertainty with another.

BBE? Please. You think this is new? We’ve known for decades that batch variability ruins bioequivalence.

But here’s the real truth - the FDA doesn’t want to fix this. Why? Because if they did, half the cheap generics would fail. And then what? People can’t afford brand-name drugs.

So they keep the 80-125 rule. They call it science. They call it progress.

It’s not. It’s a lie wrapped in a statistic.

And now you’re praising them for it? Pathetic.

Wait - you just said you’re sharing this with your support group? I’m in one too. My cousin’s on Keppra. She had three seizures last year after switching generics. They told her it was ‘stress.’ Turns out, the batch changed.

Now I’m sending this to her neurologist. Maybe they’ll finally listen.