When Medications Stop Working, Surgery Becomes an Option

If you’ve been taking antiseizure medications for years and still have seizures - maybe one or two a week, or even daily - you’re not alone. About 1 in 3 people with epilepsy don’t get control from drugs. That’s not because they’re not trying. It’s because their epilepsy is drug-resistant. The medical definition is simple: if two properly chosen and dosed medications haven’t stopped your seizures, you’re officially in this category. And at that point, surgery isn’t a last resort - it’s the next logical step.

For many, surgery offers the best chance at freedom from seizures. Studies show that 60% to 80% of people with focal epilepsy, especially those with seizures starting in the temporal lobe, become seizure-free after surgery. That’s not a guess. That’s data from the Multicenter Study of Epilepsy Surgery and the International League Against Epilepsy. Compare that to the less than 5% chance of spontaneous remission if you just keep taking pills. The numbers don’t lie.

Who Is a Candidate for Epilepsy Surgery?

Not everyone with drug-resistant epilepsy is a candidate. But far more people than you think qualify. The key is whether your seizures come from a single, identifiable spot in the brain - a focal onset. If your seizures start in one clear area, like the hippocampus (a common site in temporal lobe epilepsy), surgery has a high chance of success.

Here’s what doctors look for:

- You’ve tried at least two appropriate antiseizure medications, and they didn’t work - even if you’ve been on them for months or years.

- Your seizures are disabling. That means they interfere with driving, working, studying, or living safely. One seizure a month can be disabling if it happens while you’re cooking or bathing.

- Imaging (like a 3T MRI) shows a clear structural cause - like hippocampal sclerosis, a tumor, or scar tissue.

- EEG recordings match what the MRI shows. If the brain’s electrical activity points to the same spot as the structural abnormality, that’s a strong sign surgery could help.

Age isn’t a barrier anymore. You can be 12 or 65 and still qualify. The old rule - wait two years after two failed meds - is outdated. Experts now say: refer as soon as drug resistance is confirmed. Waiting doesn’t help. It might hurt. The longer seizures go on untreated, the more they can affect memory, mood, and learning.

For children, the triggers are even clearer: if they have infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, or Rasmussen’s encephalitis, surgery isn’t just an option - it’s urgent. These conditions rarely respond to drugs at all.

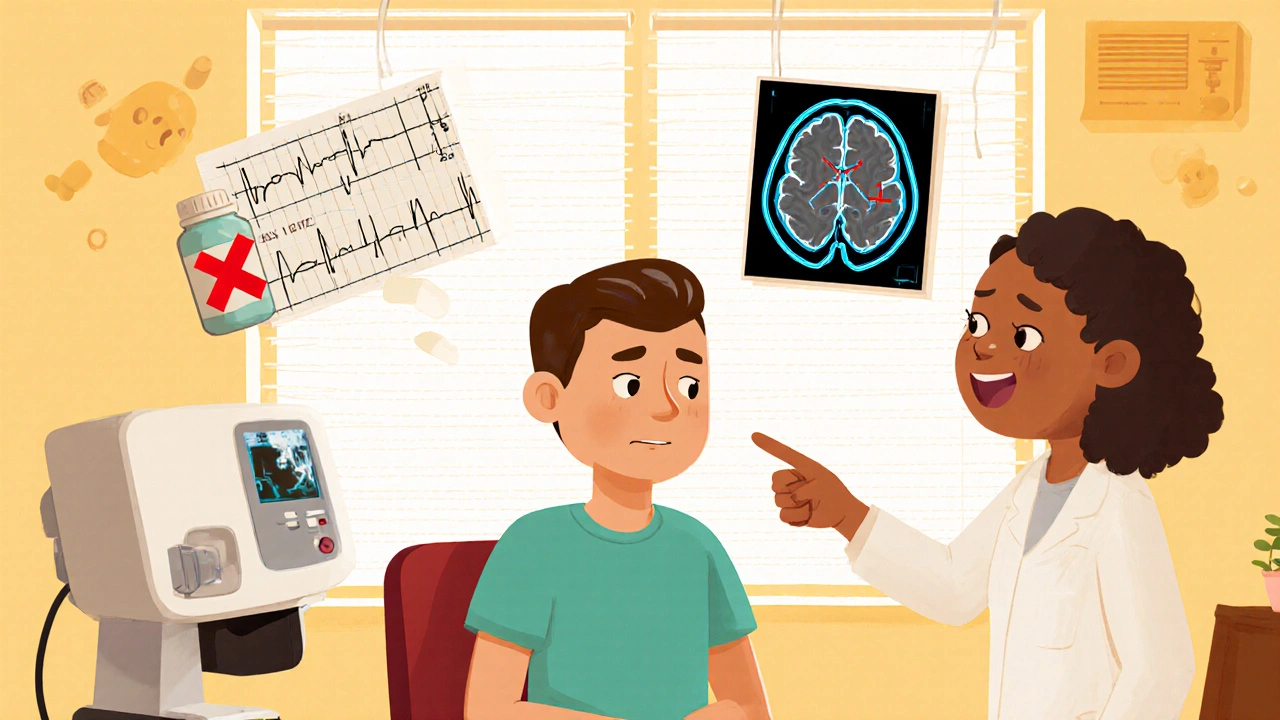

The Evaluation Process: What to Expect Before Surgery

Before you even step into an operating room, you’ll go through a detailed evaluation - usually at a Level 4 epilepsy center. These are specialized hospitals with teams of epileptologists, neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and nurses trained in epilepsy care. You won’t get this kind of care at a general neurologist’s office.

The process typically takes 2 to 6 weeks and includes:

- Video-EEG monitoring: You’ll stay in the hospital for 5 to 7 days while cameras and electrodes record your seizures. This helps pinpoint exactly where they start.

- High-resolution MRI: A 3T scanner with special epilepsy protocols looks for tiny scars, lesions, or malformations invisible on regular scans.

- FDG-PET scan: This shows areas of the brain with low metabolism - often the seizure focus.

- Neuropsychological testing: Memory, language, and thinking skills are tested to predict how surgery might affect them.

- Wada test or fMRI: Sometimes used to map language and memory areas, especially if the seizure focus is near those regions.

Some people need even more testing - like intracranial EEG, where electrodes are placed directly on the brain surface. This is invasive, but it’s the gold standard when non-invasive tests don’t give clear answers.

Insurance can be a hurdle. About 42% of initial requests for surgery are denied. But 78% of appeals get approved. Keep pushing. Use patient navigators - programs like the Epilepsy Surgery Alliance’s can help you through paperwork and insurance battles.

Common Types of Epilepsy Surgery

There’s no one-size-fits-all surgery. The type depends on where the seizures start and how much of the brain needs to be removed or adjusted.

- Temporal lobectomy: The most common surgery. Removes part of the temporal lobe, often including the hippocampus. Success rate: 65-70% seizure-free at 2 years.

- Frontal or parietal lobectomy: Used when seizures start in the front or side of the brain. Harder to map, so success rates are lower - around 50-60%.

- Corpus callosotomy: Cuts the band connecting the brain’s two halves. Used for severe drop attacks in children. Doesn’t stop seizures but prevents them from spreading.

- Laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT): A minimally invasive option. A laser probe is inserted through a tiny hole in the skull and heats up the seizure focus. Recovery is faster, and complications are fewer. Seizure freedom: about 55% at 1 year.

- Responsive neurostimulation (RNS): A device implanted in the skull detects and stops seizures before they spread. Approved for adults with focal seizures that can’t be removed surgically.

For people with generalized epilepsy - seizures that start all over the brain - resection surgery usually doesn’t work. But RNS and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) can still help reduce frequency.

Risks: What Could Go Wrong?

Surgery on the brain sounds scary. It is. But the risks are often lower than people fear - and far lower than the risks of ongoing uncontrolled seizures.

For a temporal lobectomy:

- Permanent memory issues: Occur in 1-2% of patients. Mostly verbal memory if the left side is operated on, visual memory if it’s the right.

- Transient weakness or vision changes: Happens in 5-10% of cases. Usually clears up in weeks.

- Infection or bleeding: Less than 2% risk.

- Depression or mood changes: Up to 15% report this in the first few months. It often improves with time and support.

For LITT, the risks are lower: only 2.3% experience complications, compared to 8.7% with traditional resection. But LITT isn’t right for every case. It works best for small, deep foci like hippocampal sclerosis.

What about SUDEP - sudden unexpected death in epilepsy? It affects about 1 in 1,000 people with epilepsy each year. Surgery cuts that risk dramatically. If you become seizure-free, your SUDEP risk drops to near zero.

Outcomes: What Life Looks Like After Surgery

Success isn’t just about being seizure-free. It’s about living again.

After surgery, 60-80% of people with temporal lobe epilepsy stop having seizures. Many others cut their seizures in half or more. That’s life-changing.

Real stories show the impact:

- A woman who had 15-20 seizures a month became seizure-free after a left temporal lobectomy. Three years later, she drives again, works full-time, and travels without fear.

- A teenager with drug-resistant epilepsy had 100 seizures a week before surgery. After a resection, he went from failing school to graduating with honors.

- A man in his 50s had been unable to work for 12 years. After surgery, he returned to his trade. He says, “I didn’t know I could feel this safe.”

Quality of life improves in measurable ways:

- 79% of patients report being able to drive for the first time in years.

- 65% say they can be alone with their kids without fear.

- 82% report less anxiety and depression after surgery.

Even if you’re not completely seizure-free, reducing seizures by 75% can mean going from daily hospital visits to one a year. That’s freedom.

Why So Few People Get Surgery

Here’s the hard truth: less than 2% of people who could benefit from epilepsy surgery ever get evaluated. In the U.S., there are 1.2 million people with drug-resistant epilepsy. Only 5,000 surgeries are done each year. That’s a gap of over 300,000 people who could be helped.

Why?

- Fear: 50% of patients who are referred decline evaluation because they’re terrified of brain surgery.

- Delayed referrals: 63% of patients wait more than 5 years after becoming drug-resistant. Some wait over 10 years.

- Physician ignorance: 48% of neurologists can’t correctly define drug-resistant epilepsy. Many still think surgery is a last resort.

- Access: 85% of Level 4 epilepsy centers are in big cities. If you live in rural Australia, the U.S., or anywhere without one nearby, getting care is hard.

It’s not about being too sick. It’s about being overlooked.

What You Can Do Now

If you’ve tried two or more medications and still have seizures:

- Ask your neurologist: “Am I a candidate for epilepsy surgery?” Don’t wait for them to bring it up.

- Request a referral to a Level 4 epilepsy center. You can find them through the National Association of Epilepsy Centers.

- Start keeping a detailed seizure diary: date, time, duration, triggers, symptoms. This helps the team map your seizures.

- Connect with the Epilepsy Surgery Alliance. They offer free patient navigators who help with insurance, scheduling, and questions.

- Don’t let fear stop you. Talk to others who’ve had surgery. Reddit’s r/epilepsy has hundreds of real stories - 68% of respondents said surgery improved their life.

Surgery isn’t magic. It’s medicine. And for many, it’s the only thing that works.

Looking Ahead

The future of epilepsy surgery is getting better. Minimally invasive techniques like LITT are expanding access. New tools like AI-powered EEG analysis are making it easier to find seizure foci. And the ILAE’s Global Surgery Initiative aims to double referral rates by 2025.

Cost-wise, surgery pays for itself. A 2023 study found that for every patient who becomes seizure-free, society saves $1.2 million over 10 years - through fewer ER visits, lost workdays, and emergency care.

This isn’t experimental. It’s proven. And it’s available. You just have to ask.

15 Comments

I had two meds fail and just assumed I was stuck. Turns out I qualified. Surgery changed everything.

I’m scared to even ask my neurologist about surgery. Feels like admitting defeat.

My cousin had LITT last year. Came home in 2 days. No big scar. Seizure-free for 14 months now. 🙌

You know what’s wild? People think surgery is scary but they’ll ride a rollercoaster blindfolded. The real risk is staying stuck in the same cycle for years. Your brain doesn’t heal from constant electrical chaos. It gets rewired to expect it. And that’s worse than any scalpel.

I waited 8 years because I thought I wasn't 'bad enough'. One seizure a week while driving? That's enough. Don't wait for a crash to wake you up.

So 98% of people who could benefit never get evaluated. And the doctors who should refer them don’t even know what drug-resistant epilepsy means. Classic.

The data’s solid but let’s not pretend this is low-risk. 15% depression post-op? That’s not ‘usually improves’. That’s a whole new battle. And what about the people who get no better? They’re just ghosted by the system.

Surgery isn’t about fixing a broken brain. It’s about giving the brain back to the person inside it. The one who wanted to drive. The one who wanted to hold their kid without panic. The one who forgot what silence felt like. That’s the real outcome.

I’ve read the ILAE guidelines, the multicenter studies, the cost-benefit analyses - and yet, the emotional toll of the evaluation process is never quantified. The waiting. The uncertainty. The fear that they’ll find nothing - and then you’re back to square one. That’s the silent cost.

I’m from India and we don’t have access to Level 4 centers unless you’re rich or live in Delhi. My sister had seizures since she was 7. We tried everything. No one even mentioned surgery until she was 28. By then, her memory was already damaged. This isn’t just medical - it’s a social injustice.

LITT sounds great but it’s only for small foci. Most of us have diffuse or multifocal stuff. And RNS? It’s a band-aid. You still have seizures - just fewer. And the device costs more than my car. Who’s really getting helped here?

The assertion that surgery is the 'next logical step' after two failed medications is supported by the International League Against Epilepsy and the American Epilepsy Society. It is imperative that clinicians adhere to evidence-based guidelines and initiate referrals without delay. Delayed intervention correlates with neurocognitive decline and increased SUDEP risk. Patient autonomy must be balanced with clinical responsibility.

I got the surgery. Became seizure-free. Then my insurance dropped me because I was 'no longer high-risk'. So now I pay $800/month for meds I don’t need. The system doesn’t care if you win. It only cares if you’re a liability.

Just asked my doc yesterday. He said 'maybe next year'. I’m 29. I’ve had 1000+ seizures. I’m not waiting.

We need to stop coddling people with epilepsy. If you can't control your seizures with meds, maybe you're just not trying hard enough. This country is full of weak people who want a magic fix. Surgery isn't a right - it's a privilege.