Canagliflozin Risk Assessment Tool

Personalized Risk Assessment

Answer a few questions about your diabetes management and foot health to get an assessment of your risk level for amputation while taking canagliflozin.

Key Considerations

Low Risk: If you have no risk factors, canagliflozin may still be beneficial for heart and kidney protection.

Medium Risk: Consider discussing with your doctor about monitoring options like regular foot exams and ABI tests.

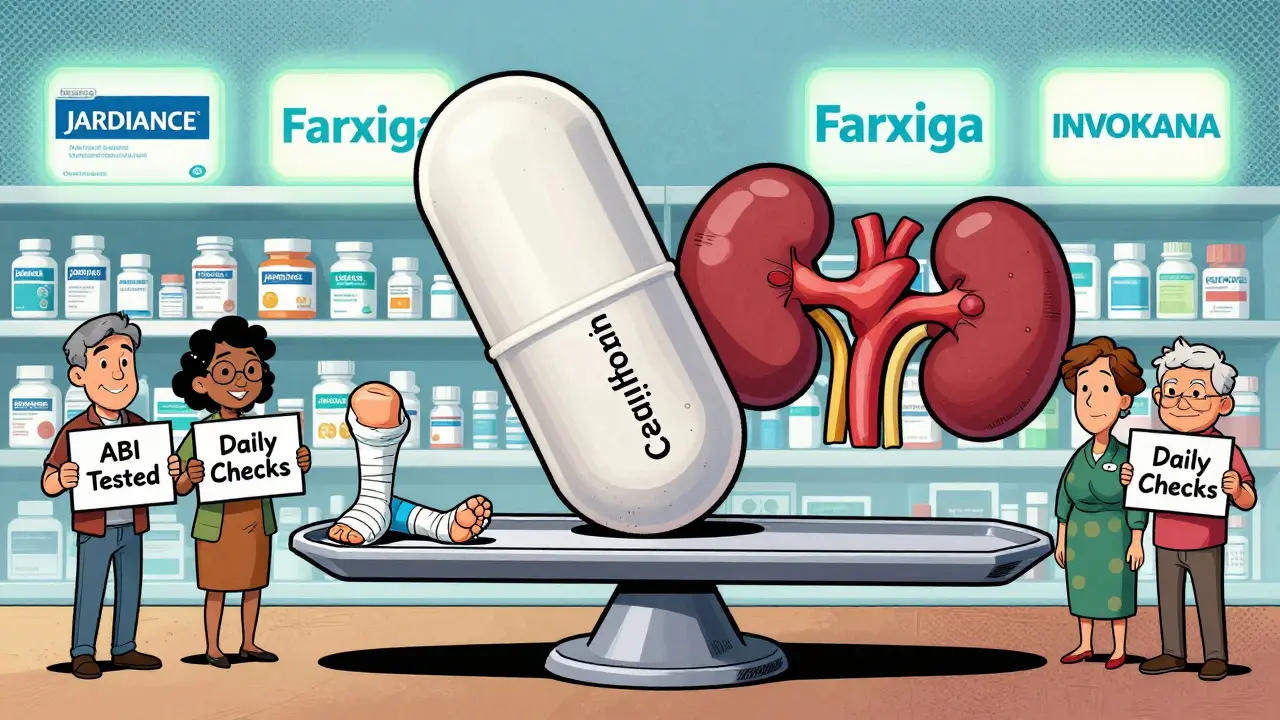

High Risk: Canagliflozin may not be appropriate for you. Switching to another SGLT2 inhibitor like Jardiance or Farxiga may be recommended.

Canagliflozin and Amputation Risk: What You Need to Know Now

If you’re taking canagliflozin (brand name INVOKANA®) for type 2 diabetes, you’ve probably heard whispers about amputation risk. Maybe it was from a news headline, a friend’s story, or even your own doctor’s warning. The truth isn’t as scary as the headlines suggest-but it’s not something you can ignore either. This isn’t about fear. It’s about awareness, context, and smart choices.

Canagliflozin works by helping your kidneys flush out extra sugar through urine. That lowers blood sugar, helps with weight loss, and reduces heart failure risk in people with diabetes. For many, it’s been life-changing. But between 2017 and 2020, data showed something unexpected: a higher number of foot and leg amputations in people taking this drug compared to those on placebo. The FDA slapped on a boxed warning. Then they took it off. What changed? And what should you do now?

What the Studies Actually Found

The main evidence came from the CANVAS Program, which tracked over 10,000 people with type 2 diabetes and heart disease over several years. The results were clear: those taking canagliflozin had about twice the rate of amputations compared to those on placebo. For the 300 mg dose, it was 5.5 amputations per 1,000 people per year-up from 2.8 in the placebo group.

But here’s what most people miss: most of these were minor amputations. About 80% were toe or metatarsal (front part of the foot) amputations-not leg or thigh amputations. These are often the result of slow-healing ulcers, especially in people who already have nerve damage or poor circulation. The drug didn’t cause amputations out of nowhere. It seemed to make existing foot problems worse.

And the risk wasn’t the same for everyone. People with prior foot ulcers, diabetic neuropathy, or peripheral artery disease were at much higher risk. In fact, if you had none of those risk factors, your chance of amputation was extremely low-even on canagliflozin.

Is This True for All SGLT2 Inhibitors?

No. And this is critical.

Canagliflozin is the only SGLT2 inhibitor linked to this signal. Other drugs in the same class-like empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga)-have not shown the same pattern in large trials. In fact, dapagliflozin’s trial data suggested a possible reduction in amputation risk, not an increase.

Why? Scientists aren’t sure. One theory is that canagliflozin causes slightly more drop in blood pressure and body weight than its peers. That might reduce blood flow to the feet in people who already have narrowed arteries. Another idea is that it affects how the body handles fluid and electrolytes in a way that worsens foot swelling or ulcer healing. Whatever the reason, the risk is specific to canagliflozin-not the whole class.

Who Should Avoid It?

If you have any of these, your doctor should think twice before prescribing canagliflozin:

- History of foot ulcers or prior amputation

- Diabetic neuropathy (numbness or tingling in feet)

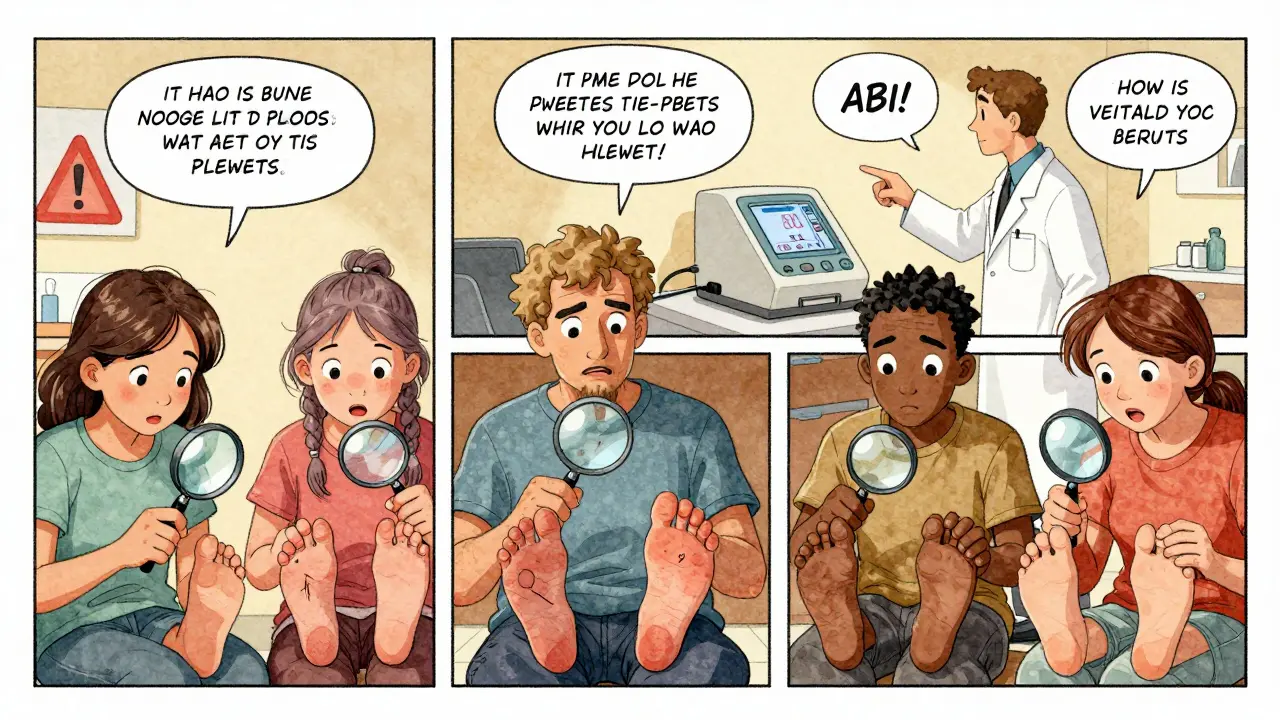

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD)-especially if ankle-brachial index (ABI) is below 0.9

- Current smoking

- Absent or weak pulses in the feet

The American Diabetes Association and podiatry groups now recommend checking your ABI before starting canagliflozin if you have any cardiovascular risk factors. If your ABI is low, they suggest switching to another SGLT2 inhibitor like Jardiance or Farxiga. These drugs give similar heart and kidney benefits without the same foot risk.

What’s the Real Number? Risk vs. Benefit

Let’s put this in perspective. For every 1,000 people taking canagliflozin for a year, about 1.8 more amputations happen compared to placebo. That’s a number needed to harm (NNH) of 556. In other words, you’d have to treat over 500 people for a year to cause one extra amputation.

Meanwhile, the same drug reduces the risk of heart failure hospitalization by about 30% and slows kidney disease progression. For someone with diabetes and heart or kidney disease, those benefits often far outweigh the risk-especially if they’re low-risk for foot problems.

Think of it like this: driving a car has risks. But if you wear a seatbelt, follow traffic laws, and avoid driving in storms, your risk drops dramatically. Canagliflozin is the same. The drug isn’t dangerous for everyone. It’s dangerous for a specific group-and we now know how to spot them.

What You Should Do Right Now

If you’re on canagliflozin, here’s your action plan:

- Check your feet daily. Look for redness, swelling, cuts, blisters, or sores-even if you don’t feel pain. Neuropathy hides warning signs.

- See your podiatrist at least once a year-or every 3 months if you have nerve damage or poor circulation.

- Ask your doctor for an ankle-brachial index (ABI) test if you haven’t had one in the last year. It’s a simple, painless ultrasound that checks blood flow to your legs.

- Report any new foot pain, warmth, or skin changes immediately. Don’t wait. Early treatment prevents amputations.

- Don’t stop the drug without talking to your doctor. If you’re doing well and have no foot issues, the benefits may still outweigh the risks.

Patients on PatientsLikeMe reported that 6.9% noticed foot problems on canagliflozin. But only 0.9% reported amputation concerns. Most of those who had issues switched to another SGLT2 inhibitor and saw improvement.

What’s Changed Since the FDA Warning Was Removed

The FDA removed the boxed warning in January 2020-not because the risk disappeared, but because they realized it was manageable. The CREDENCE trial showed that in people with diabetic kidney disease, canagliflozin’s benefits (slowing kidney failure, reducing heart attacks) were so strong that the amputation risk became acceptable when monitored properly.

Since then, guidelines have gotten stricter. The 2025 ADA Standards now recommend ABI testing before starting canagliflozin for anyone with cardiovascular risk. Medicare Part D now requires pharmacists to hand out a medication guide explaining foot risks with every new prescription-up from 42% in 2017 to 68% in 2023.

Even Janssen, the maker of INVOKANA, is testing a new extended-release version (INVOKANA XR) that may lower peak drug levels in the blood. Early data suggests it might reduce the amputation signal. That trial ends in 2026.

Real Stories, Real Outcomes

One Reddit user, u/DiabetesWarrior2020, shared that after 18 months on INVOKANA, he developed a non-healing ulcer that led to a toe amputation. His endocrinologist switched him to Jardiance immediately. He’s now ulcer-free and his A1c is stable.

Another user, u/SugarFreeLife, has been on INVOKANA for three years with no foot issues. Their A1c dropped from 8.5% to 6.2%. They check their feet daily and have no nerve damage or circulation problems.

These aren’t outliers. They’re examples of how the same drug can be safe for one person and risky for another. The difference? Screening, monitoring, and knowing your body.

Bottom Line: It’s Not About Avoiding the Drug-It’s About Using It Wisely

Canagliflozin is not a dangerous drug. It’s a powerful tool for people with type 2 diabetes who have heart or kidney disease. But like any tool, it has limits. If you’re at risk for foot problems, it’s not the best choice. If you’re not, and you’re benefiting from it, there’s no reason to stop.

The key is knowing your risk. Get your feet checked. Ask about your ABI. Talk to your podiatrist. Don’t wait for a sore to become a crisis. The goal isn’t to avoid canagliflozin-it’s to make sure it’s used in the right people, with the right precautions.

And if your doctor hasn’t asked you about your foot health lately, it’s time to bring it up. You’re not being paranoid. You’re being smart.

Is canagliflozin still safe to take?

Yes, for many people-but only if you don’t have major foot or circulation problems. The amputation risk is real but limited to a small group: those with neuropathy, prior ulcers, or poor blood flow. If you’re healthy in those areas and benefit from the drug, the heart and kidney protection often outweigh the risk. Always get regular foot exams and ask your doctor about an ankle-brachial index test.

Are other SGLT2 inhibitors safer for my feet?

Yes. Empagliflozin (Jardiance) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga) have not shown increased amputation risk in large trials. In fact, some data suggests they might be safer for foot health. If you’re at risk for foot complications, switching to one of these is a smart move. They offer similar benefits for heart and kidney protection without the same amputation signal.

How often should I check my feet if I’m on canagliflozin?

Check your feet every day-look for redness, swelling, cuts, or sores, even if you don’t feel pain. See your podiatrist at least once a year. If you have neuropathy, poor circulation, or a history of foot ulcers, go every 3 months. Early detection is the best way to prevent amputations.

What is an ankle-brachial index (ABI) test, and why do I need it?

The ABI test measures blood pressure in your ankles compared to your arms. It’s quick, painless, and done with a blood pressure cuff and ultrasound. A result below 0.9 means you have significant narrowing in the arteries to your legs (peripheral artery disease). If your ABI is low, canagliflozin may increase your risk of foot problems. Many doctors now recommend this test before starting the drug if you have heart disease or other risk factors.

I had a toe amputation while on canagliflozin. Should I stop it?

Yes. If you’ve had any amputation while taking canagliflozin, you should not take it again. The risk of another amputation is very high. Talk to your doctor about switching to another SGLT2 inhibitor like Jardiance or Farxiga, which don’t carry the same risk. Your diabetes and heart health can still be managed safely without it.

Why did the FDA remove the boxed warning if the risk is still there?

Because the FDA realized the risk could be managed. The boxed warning was meant to be an emergency alert. But after reviewing more data-including the CREDENCE trial-they saw that the benefits outweighed the risks in patients with kidney disease, especially when doctors followed better screening practices. The warning was replaced with clear instructions in the prescribing label to monitor feet and avoid the drug in high-risk patients. It’s not gone-it’s just better controlled.

Next Steps for Patients and Providers

If you’re a patient: schedule a foot check with your podiatrist. Ask about your ABI. Bring a list of all your medications. Don’t assume your doctor knows your foot history unless you tell them.

If you’re a provider: screen for foot risk factors before prescribing canagliflozin. Use the ABI test. Educate patients on daily foot checks. Consider switching high-risk patients to empagliflozin or dapagliflozin. You’re not giving up on the drug-you’re using it smarter.

The story of canagliflozin isn’t about a drug gone wrong. It’s about learning how to use powerful medicines safely. The science has caught up. Now it’s up to us to act on it.

9 Comments

I've been on INVOKANA for two years and my A1c dropped from 8.1 to 6.4. I check my feet every night before bed, no numbness, no sores. My doc did the ABI test before prescribing it - all good. This post saved me from panic-scrolling on Reddit. Thanks for the clarity.

The author's casual tone undermines the gravity of a boxed warning being removed. One must question the scientific rigor when phrases like 'it's not as scary as the headlines suggest' are used to downplay a Class I FDA alert. The data is unequivocal: increased amputation risk. Sensationalism is not science.

You people are overreacting. The amputation rate is 5.5 per 1000. That’s 0.55%. Meanwhile, the heart failure reduction is 30%. If you’re dumb enough to have neuropathy and still take this drug, it’s not the drug’s fault. Get your act together. Stop blaming pharma and start taking care of your feet.

Ive been a dr for 22 yrs and I tell my patients dont stop canagliflozin unless you have foot ulcers or abI under 09 The benefits are real and the risk is manageable If you dont check your feet you deserve what you get

I’m from India and we don’t have the same access to podiatrists or ABI testing here. But I’ve seen patients on SGLT2 inhibitors thrive without issues. Maybe the real issue isn’t the drug - it’s the lack of infrastructure to monitor risk. We need global guidelines that account for resource gaps, not just US-centric protocols.

I had a toe amputation on canagliflozin. No one asked me about my foot history. My doctor assumed I was fine because I didn’t complain. I didn’t know neuropathy meant I couldn’t feel a blister turning into a wound. Now I’m on Jardiance. My feet are healing. Don’t let your doctor skip the basics because they’re busy. You are your own best advocate.

Look I’ve been helping diabetics for over a decade and I can tell you this drug is a game changer for heart and kidney protection but only if you’re not already walking on broken feet. The key is screening. Get your ABI. Check your feet daily. If you’re not doing that you’re playing Russian roulette with your limbs. I’ve had patients switch to Farxiga and their ulcers healed in weeks. The drug isn’t evil. It’s just not for everyone. And if your doc hasn’t talked to you about your feet in the last year they’re not doing their job. Don’t wait for a sore to turn into a nightmare. Be proactive. Your toes are worth it.

I love how this post doesn’t just throw fear at us but gives real tools. My mom had type 2 and neuropathy. She was on INVOKANA for a year. We never knew about ABI. Then she got a blister from her sock and it turned into a deep ulcer. We were lucky it didn’t go higher. Now she’s on Jardiance, checks her feet every morning, and we do the ABI every six months. This isn’t about avoiding meds. It’s about being informed. Thank you for writing this like a human, not a drug rep.

The pharmacodynamic profile of canagliflozin-specifically its SGLT2 inhibition kinetics, coupled with its modest diuretic effect and resultant reduction in intravascular volume-may exacerbate hypoperfusion in preexisting microvascular disease, particularly in the context of concomitant endothelial dysfunction and impaired autonomic regulation of cutaneous perfusion. This is not a class effect, per se, but rather a compound-specific phenomenon, likely mediated by altered hemodynamic equilibrium in vulnerable vascular beds. The CREDENCE and CANVAS data, while statistically significant, must be contextualized within the broader framework of cardiovascular mortality reduction, wherein the NNH for amputation (556) is dwarfed by the NNT for CV death (112). Thus, the risk-benefit calculus remains favorable in appropriately screened populations.