When you take a pill, it doesn’t just disappear into your bloodstream. What you ate-or didn’t eat-before taking it can change how much of the drug actually gets absorbed. This isn’t speculation. It’s science. And it’s why regulators like the FDA and EMA require fasted vs fed state testing for nearly every new oral medication. The difference between taking a drug on an empty stomach versus after a meal can mean the difference between it working-or failing.

What Fasted and Fed States Really Mean

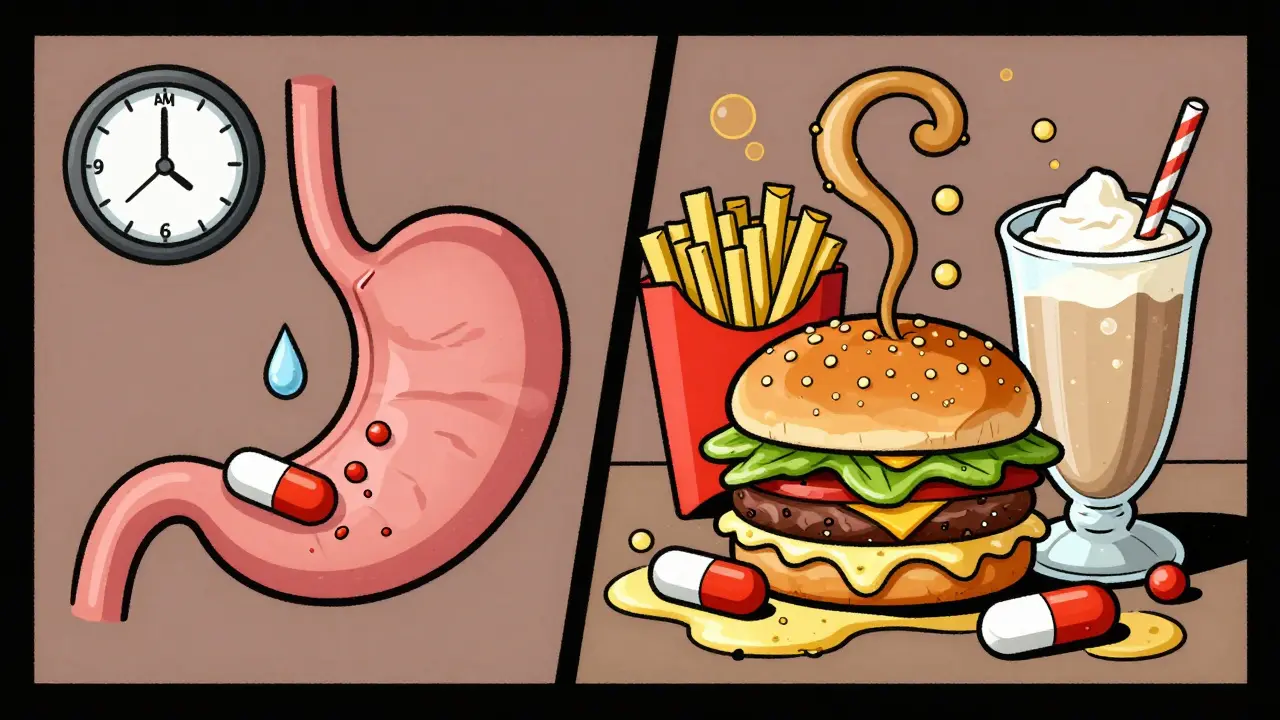

Fasted state means no food for at least 8 to 12 hours. Water is allowed. No coffee, no gum, no snacks. Fed state means you’ve eaten a standardized meal-usually high in fat and calories-about 2 to 4 hours before taking the drug. In pharmaceutical trials, that meal isn’t just any breakfast. It’s carefully measured: 800-1,000 calories, with 500-600 of them coming from fat. That’s like a double cheeseburger, large fries, and a milkshake.

Why such a specific meal? Because fat slows down gastric emptying. It changes the pH inside your stomach. It triggers bile release. All of this affects how drugs dissolve and get absorbed. Studies using SmartPill capsules show gastric residence time jumps from under 14 minutes in a fasted state to nearly 80 minutes when you’ve eaten. That’s a five-fold increase. And pH? It drops from 2.5 to as low as 1.5. These aren’t small changes. They’re game-changers for drug absorption.

Why the Food Effect Can Make or Break a Drug

Not all drugs react the same way to food. Some absorb better with it. Others absorb worse. Take fenofibrate, a cholesterol-lowering drug. In fed state, its bioavailability spikes by 200-300%. If you took it fasted, you’d get barely half the dose you need. That’s dangerous. On the flip side, griseofulvin-an antifungal-sees its absorption drop by 50-70% when taken after a meal. Take it with food, and it might not work at all.

This is why dual-state testing is mandatory. A drug can’t be approved unless manufacturers prove it works safely and consistently under both conditions. The FDA’s 1997 guidance made this official. By 2021, the EMA expanded the rule: if you don’t know how food affects your drug, you test it. And 35% of drugs reviewed in 2019 showed clinically significant food effects. That’s more than one in three.

The Real-World Impact on Patients

Imagine you’re prescribed a medication that works best when taken with food. You’re in a hurry. You grab the pill and swallow it with a sip of water before leaving for work. You don’t feel better. You think the drug isn’t working. You stop taking it. Weeks later, your condition worsens. This isn’t rare. It’s predictable.

Or consider a patient on a narrow therapeutic index drug-where the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is tiny. If food boosts absorption by more than 20%, as FDA pharmacologist Dr. Lawrence Lesko warned in 2019, you risk overdose. That’s why these tests aren’t just bureaucratic hoops. They’re safety checks.

And it’s not just about Western populations. In 2022, research showed Asian subjects empty their stomachs 18-22% slower than Caucasians after eating. That means the same meal could lead to higher drug levels in one group and lower in another. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now requires testing across diverse ethnic groups. Precision medicine isn’t just a buzzword-it’s a regulatory requirement.

Fasted vs Fed in Exercise: A Parallel Story

While the pharmaceutical world uses fasted and fed states to test drugs, exercise science uses the same framework to test human performance. The parallels are striking. Fasted exercise-after 8-12 hours without food-boosts fat oxidation by 30-50%. Free fatty acids in the blood rise sharply. Mitochondrial adaptations improve. That’s why some endurance athletes and keto followers swear by it.

But here’s the catch: high-intensity performance drops by 12-15% in the fasted state. Your muscles need glycogen. Without it, you can’t sprint, lift heavy, or push through intervals. Fed-state exercise, with 1-4 grams of carbs per kilogram of body weight eaten 1-4 hours before, supports better power output and endurance. A 2018 meta-analysis of 46 studies found fed-state exercise improved prolonged aerobic performance by 8.3%-but only if the workout lasted longer than 60 minutes.

Even here, individual variation matters. Genetic differences in the PPARGC1A gene explain up to 33% of how someone responds to fasted vs fed training. One person burns fat like a furnace fasted. Another crashes. That’s why blanket advice like “always train fasted for fat loss” is misleading. Context is everything.

Why Both Conditions Are Non-Negotiable

Some argue: “Why test both? Most people eat before taking their meds.” But that’s the point. Real people don’t follow perfect protocols. Some take pills on an empty stomach by accident. Others eat a heavy meal right before. The goal isn’t to simulate an ideal world-it’s to understand what happens in the messy, real one.

Pharmaceutical companies don’t test both states because they’re being cautious. They do it because regulators demand it. And they demand it because the data is too clear to ignore. A drug that works great fasted but fails when taken with food? That’s a liability. A drug that’s unpredictable across populations? That’s a public health risk.

The same logic applies to fitness. You wouldn’t judge an athlete’s strength based only on morning workouts. You’d test them after rest, after carbs, after sleep deprivation. Why? Because performance is context-dependent. So is drug absorption.

What This Means for You

If you’re prescribed an oral medication, read the label. Does it say “take on an empty stomach”? Then don’t eat for two hours before and after. Does it say “take with food”? Then don’t skip the meal. That’s not just advice-it’s part of the drug’s design.

And if you’re into fitness, don’t treat fasted training like a magic bullet. It has benefits for fat metabolism, yes. But it’s not superior for muscle gain, strength, or high-intensity workouts. If you’re training for performance, eat first. If you’re training for metabolic health, fasted might help-but only if you’re not feeling dizzy or weak.

The bottom line? Your body doesn’t operate in a vacuum. Whether you’re taking a pill or hitting the gym, what you’ve eaten matters. And ignoring that fact isn’t just risky-it’s outdated.

What’s Next?

The field is moving toward even more precision. The EMA is now requiring continuous glucose monitoring during fed-state trials to track real-time metabolic responses. Exercise science is using genetic testing to match training protocols to individual biology. The future isn’t about one-size-fits-all. It’s about understanding how your unique physiology responds to food-and using that knowledge to make better decisions.

Whether you’re a patient, an athlete, or a clinician, the message is the same: fasted and fed states aren’t just lab conditions. They’re real-life variables. And they matter more than you think.

Why do some medications say to take them on an empty stomach?

Some drugs are absorbed better when there’s no food in the stomach. Food can block absorption, slow gastric emptying, or change stomach pH, reducing how much of the drug enters your bloodstream. For example, antibiotics like tetracycline bind to calcium in dairy, making them ineffective. Taking them fasted ensures maximum absorption.

Can I just take my pill with a snack if the label says fasted?

No. Even a small snack can interfere. A banana, a handful of nuts, or a glass of milk can be enough to alter absorption. If the label says fasted, wait at least two hours after eating and don’t eat for another hour after taking the pill. Small deviations can lead to underdosing or unpredictable effects.

Does eating before exercise help with fat loss?

Not necessarily. While fasted exercise burns more fat during the workout, studies show no difference in long-term fat loss between fasted and fed training over weeks or months. Total calorie balance matters more than when you eat. Fasted training might help metabolic health, but it won’t magically burn more body fat.

Why do drug trials use such a high-fat meal for fed-state testing?

A high-fat meal creates the strongest possible food effect. It slows digestion, increases bile flow, and raises stomach pH-maximizing the chance to detect changes in drug absorption. If a drug works under these extreme conditions, it’s likely to work under normal ones too. It’s a worst-case scenario test.

Is fasted training better for everyone?

No. Fasted training can reduce workout intensity by 12-15%, increase dizziness, and impair recovery. It’s best suited for low-to-moderate intensity sessions in people focused on metabolic health-not athletes training for performance. If you feel weak or lightheaded, eat before working out. Your body’s response matters more than trends.

How do I know if my medication is affected by food?

Check the prescribing information or package insert. Look for phrases like “take on an empty stomach,” “take with food,” or “food may affect absorption.” If it’s unclear, ask your pharmacist. They can tell you whether food interaction studies were done and what the results mean for you.

10 Comments

Okay but let’s be real - if you’re taking your meds with a bag of chips and a soda, you’re not just messing with absorption, you’re playing Russian roulette with your liver. The FDA doesn’t make these rules because they hate fun. They make them because someone died because their statin didn’t work and they thought ‘it’s just a snack’.

So basically the pharmaceutical industry spent billions proving that food affects pills. Groundbreaking. Next they’ll tell us water is wet.

bro i took my blood pressure med with a burrito and i felt like a god 😎💊🤯 maybe the system is broken???

35% of drugs show clinically significant food effects. That’s not a bug. That’s the system working.

This is actually one of the most important yet overlooked topics in medicine. I’ve seen patients stop their meds because they didn’t feel anything - not because the drug failed, but because they took it wrong. It’s not about discipline. It’s about education. We need clearer labels, simpler instructions, and maybe even QR codes on bottles that link to short videos showing how to take it properly.

As someone from India, where meals vary wildly in composition - from spicy lentils to fried snacks - the idea of a standardized high-fat meal for clinical trials feels almost comical. Yet, the science holds. I’ve watched my father’s cholesterol levels fluctuate simply because he took his fenofibrate after chai and paratha instead of plain water. This isn’t Western medicine being rigid - it’s medicine being precise.

Why do we let corporations dictate how we eat? If a drug needs a greasy burger to work, maybe the drug is the problem - not the person. The whole system is rigged to sell pills, not heal people.

I used to think fasted workouts were the holy grail… until I passed out on the treadmill. Now I eat a banana before I lift. No shame. My gains didn’t disappear. My brain didn’t melt. Sometimes the simplest fix is just… eating.

People think science is about facts but it’s really about control. They want to control how you eat so they can control how your body reacts. They test on fat meals because they want to make sure no one ever gets the full effect unless they follow the rules. That’s not science. That’s power dressed up as safety.

Did you know that in some cultures, fasting isn’t just religious - it’s economic? People take meds on empty stomachs not because they’re following guidelines, but because they had nothing to eat. The FDA’s protocols assume wealth. That’s why global drug efficacy varies. It’s not biology - it’s capitalism.