When more generic drugs enter the market, prices don’t always drop - and sometimes they don’t drop at all

You’d think the more generic versions of a drug that hit the market, the cheaper they’d get. After all, competition drives prices down - that’s basic economics. But in the real world of pharmaceuticals, that simple rule often breaks down. You can have five, six, even ten generic makers selling the same pill, and the price might still be stuck at $100 a month. Why? It’s not about supply. It’s about strategy.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that generic drugs saved Americans over $3 trillion between 2000 and 2023. That’s real money. Generics now make up 90.3% of all prescriptions filled. But they only account for 23.4% of total drug spending. That gap tells you something: generics are everywhere, but they’re not always cheap.

The first generic doesn’t mean instant savings

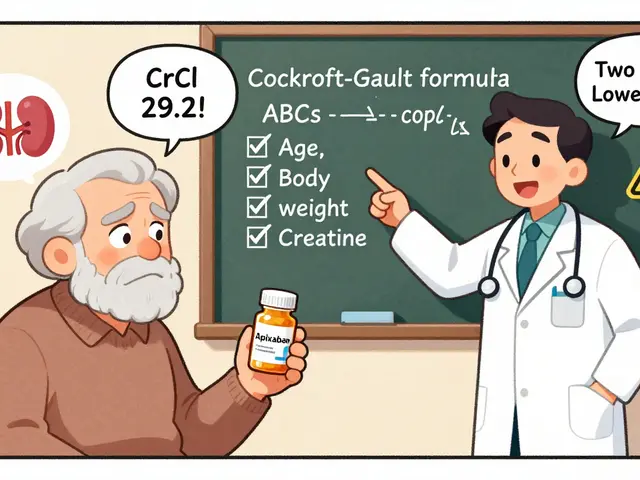

The moment a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the first generic manufacturer gets a 180-day exclusivity period. During that time, they’re the only one allowed to sell the generic. That’s a huge advantage. They often capture 80% of the market. And because they’re the only game in town, they don’t always slash prices right away. Some hold off, waiting to see what others will do.

That’s the first twist: the first generic isn’t always the cheapest. It’s often the one with the best distribution deal, the strongest relationship with a Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM), or the one that got lucky with timing. PBMs control 90% of drug purchases in the U.S. They don’t always pass savings on to patients. They care about rebates, not retail prices.

More competitors don’t always mean lower prices

Here’s where things get strange. The FDA says that when you have six or more generic makers, prices drop by 95% compared to the brand-name version. That sounds amazing - until you look at real data.

A 2023 study in China found that 15 out of 27 brand-name drugs still held over 70% of the market eight quarters after generics entered. Even more surprising: 70.4% of those drugs had only one or two generic competitors, despite no legal barriers to more. Why? Because entering the market is expensive. You need to prove your pill is identical to the brand - not just in ingredients, but in how it dissolves, how it’s absorbed, how it behaves in the body. That’s called proving Q1, Q2, Q3 - critical quality attributes. Only big manufacturers can afford the testing. Small companies get scared off.

And when companies do enter, they don’t always compete aggressively. In Portugal, researchers found that even with multiple generic makers, prices stayed near the government’s price cap. Why? Because the companies knew each other too well. They competed across dozens of drugs. If one lowered the price on a statin, the others would follow - but only to the cap. No one wanted to start a price war that would hurt everyone. That’s called mutual forbearance. It’s not collusion. It’s just smart business in a crowded, regulated space.

Brand-name companies fight back - sometimes by raising prices

Here’s the real kicker: brand-name companies don’t just sit back and watch their market disappear. In China, 24 brand-name makers lowered prices by an average of 3% after generics entered. But 3 of them actually raised prices - by 0.62% on average. How? By convincing doctors and patients that their version was “better.” Maybe it had a different coating. Maybe it came in a fancier bottle. Maybe the sales reps were just better trained.

Patients don’t always care about the chemical formula. They care about what their doctor says. If a doctor says, “Stick with the brand - it’s more reliable,” the brand keeps selling. And if the brand has a strong reputation - like for cancer drugs such as imatinib or dasatinib - patients and insurers are willing to pay more. That’s why some originator drugs still hold onto market share even when generics are cheaper.

Authorized generics: the secret weapon

Here’s another twist: sometimes the brand-name company itself launches a generic version. That’s called an authorized generic. It’s not a different drug. It’s the exact same pill, just sold under a different label. The brand does this during its 180-day exclusivity window to squeeze out other generics.

When the brand owns the authorized generic, wholesale prices drop by 8-12%. But here’s the catch: if a different company owns the authorized generic, the brand’s price goes up - by 22%. Why? Because the brand feels threatened. It’s not just competing with generics. It’s competing with a rival that has inside knowledge of its own product.

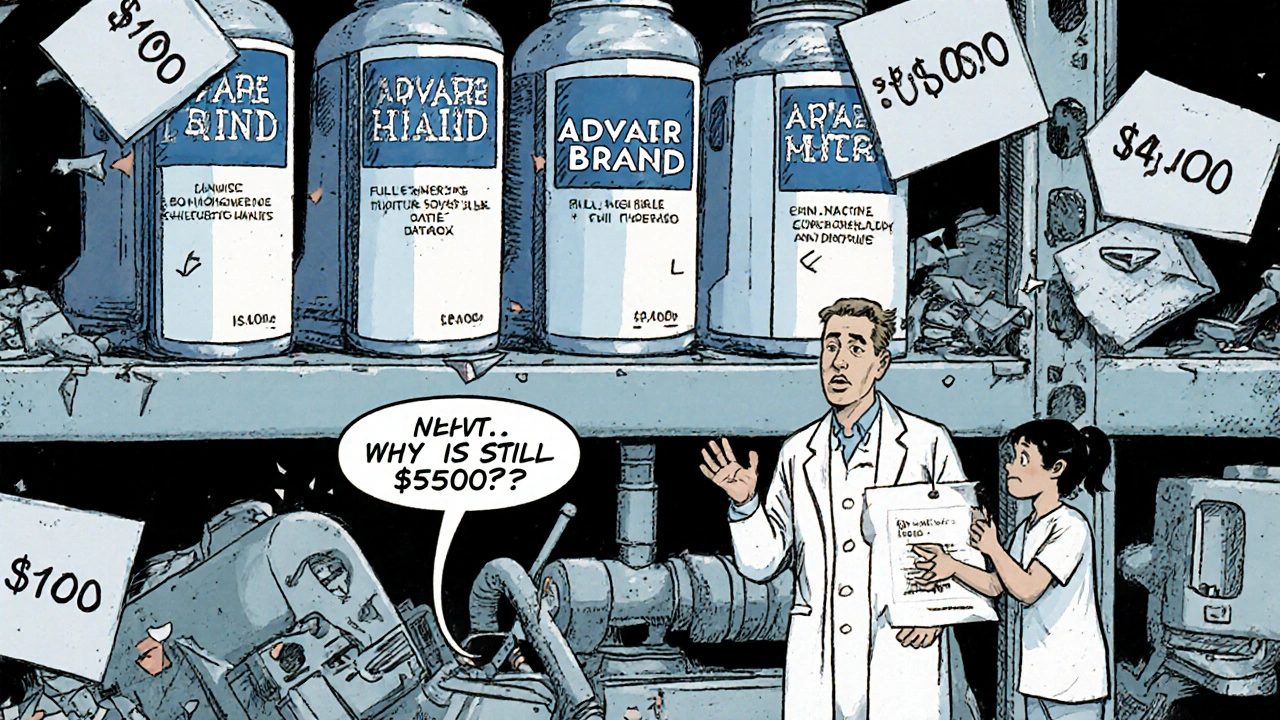

Complex drugs = less competition

Not all drugs are created equal. Simple pills - like metformin or lisinopril - have dozens of generic makers. But complex drugs? Think inhalers, injectables, or topical creams with special delivery systems. These require expensive testing to prove they’re identical to the brand. Only a handful of companies have the tech and cash to do it.

DrugPatentWatch found that complex generics can cost $10 million or more to develop. That’s why you’ll see only two or three makers for a drug like Advair or Humira - even years after the patent expires. The market isn’t blocked by law. It’s blocked by cost.

More competitors mean fewer shortages

There’s one big win from multiple generic makers: supply. The FDA found that drugs with three or more manufacturers had 67% fewer shortages between 2018 and 2022. That’s huge. When one factory has a problem - contamination, equipment failure, raw material shortage - another can step in. But if only one company makes the generic? One hiccup means a nationwide shortage. That’s why some hospitals and pharmacies push for multiple suppliers, even if the price is slightly higher.

The Inflation Reduction Act is changing the game

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for some of the most expensive brand-name drugs. That’s good for patients. But it’s creating a new problem for generics.

Generic manufacturers don’t make money off low prices. They need enough revenue to cover costs and make a profit. If Medicare sets a Maximum Fair Price (MFP) for a brand drug at $50 a month, and the generic is already selling for $45, why would a company invest millions to enter that market? The answer: they won’t. Lumanity’s 2023 analysis warns this could lead to fewer generics entering the market - especially for high-cost drugs like insulin or cancer treatments. That’s the opposite of what the law intended.

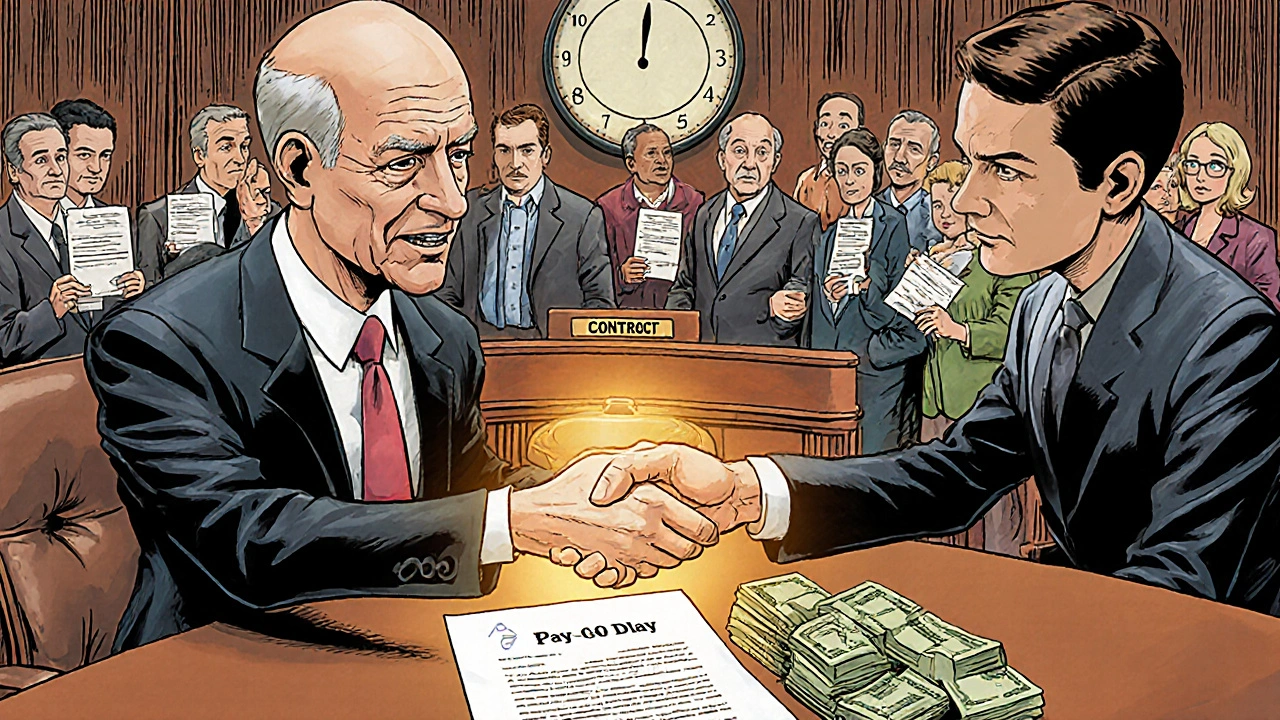

Patents aren’t just about protection - they’re about delay

Brand-name companies don’t just rely on one patent. They file dozens - covering everything from the pill’s shape to how it’s packaged. These are called “secondary patents.” They don’t protect the active ingredient. But they can block generics anyway.

Generic companies spend years fighting these patents in court. Sometimes, they settle. The brand pays the generic to delay entry. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” deal. The FTC has cracked down on these, but they still happen. And when they do, patients wait months or years for cheaper options - even after the main patent expires.

What does this mean for you?

If you’re paying for a generic drug and it’s still expensive, you’re not imagining it. The system is broken - not because there aren’t enough makers, but because the rules don’t always reward competition. Here’s what you can do:

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there another generic maker for this?” Sometimes, switching brands lowers the price.

- Check GoodRx or SingleCare. Prices vary wildly between pharmacies.

- If your drug is on Medicare, ask if it’s subject to price negotiation. You might get a better deal.

- Don’t assume the brand is better. For most drugs, generics are just as safe and effective.

The bottom line: more generic competitors don’t guarantee lower prices. But they do guarantee more choices - and that’s the only thing that can eventually force the system to change.

Why some drugs still cost a fortune - even with generics

Let’s say you need a drug for high blood pressure. There are 12 generic versions. Shouldn’t the price be a dollar a pill? Not if the brand still controls the distribution channels. Not if PBMs don’t want to pass savings to you. Not if the generic makers are too scared to undercut each other. Not if the drug is complex, or if the brand convinced doctors it’s “superior.”

It’s not about how many companies make the drug. It’s about who controls the system. And right now, that’s not the patient. It’s not even the generic maker. It’s the middlemen - PBMs, insurers, pharmacy chains - and the legal and regulatory structures that let them decide who wins and who loses.

What’s next for generic competition?

The next frontier isn’t pills. It’s biologics - complex drugs made from living cells. These are the new expensive drugs: for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes. They’re harder to copy. The FDA says the 85% price drop we saw with simple generics won’t happen here. Biosimilars - the generic version of biologics - cost $100 million or more to develop. Only a few companies can do it.

That means even with multiple competitors, prices will stay high. And without real price pressure, patients will keep paying more.

The system needs a reset. Not more patents. Not more loopholes. But real rules that force competition to work - not just on paper, but in the pharmacy.

8 Comments

This is why I don't trust any of these pharma bros. They're all in on the scam. More generics? Yeah right. It's just a new way to split the pie. PBMs are the real villains here - they're the ones hoarding the savings while we pay $100 for metformin. Wake up, America! This isn't capitalism, it's corporate feudalism. 😤

The Q1/Q2/Q3 bioequivalence requirements are the real bottleneck. Most people don't realize that dissolution profiles and particle size distribution aren't just regulatory busywork - they're pharmacokinetic gatekeepers. Small players can't afford the analytical instrumentation needed to prove comparability, especially for complex formulations like extended-release or inhaled drugs. The 10M R&D cost isn't inflated - it's conservative.

Okay so let me get this straight - the system is so broken that the ONLY thing keeping drugs affordable is the fact that companies are too chicken to actually compete? Like, we have TEN manufacturers but they're all just sitting there like a group of toddlers in a sandbox where no one wants to be the first to share their toy? And the brand names are out here raising prices because someone used a different color coating? I mean... I'm not mad, I'm just disappointed. This isn't a market, it's a sitcom written by a lobbyist. And the FDA? They're the punchline. 🤡

So let me get this right... you're telling me that after all these years of screaming about competition driving prices down... the market just decided to take a nap? Like, sure, we got 12 versions of lisinopril but they're all priced at $47 because no one wants to be the one to start the price war? And the brand? Oh they just casually raised prices by 0.62% because their sales rep wore a nicer tie? Honey. I'm not even mad. I'm just impressed. The system is so broken it's art. 🙃

I just checked my prescription and it's $42 at CVS but $18 at Walmart. Why does no one talk about this? The pharmacy is literally the wild west. You gotta play the game. GoodRx saved me $200 last month. Stop blaming the generics. Blame the middlemen who don't even know your name but charge you extra for breathing.

This is all part of the deep state pharma agenda. Did you know the FDA is secretly owned by Pfizer? The whole generic system is a psyop to make us think we have choices. The real reason prices don't drop is because the government is using the drug supply chain to track our biometrics through the pills. That's why they allow so many generics - to normalize the surveillance. And the Inflation Reduction Act? That's just the first step before they start injecting nanochips into insulin. I told my doctor. He laughed. He doesn't know what's coming.

In Nigeria we see this same pattern with antibiotics. More companies don't mean cheaper. It means more fake pills on the market. The real issue isn't competition - it's trust. When you don't know if the generic you're buying is actually the same pill, you pay more for the brand even if it's not better. People aren't irrational. They're just trying not to die. The system needs to fix the quality control first. Price is secondary.

This is actually really hopeful if you think about it. Even with all the broken incentives, multiple manufacturers still prevent shortages. That’s huge. Imagine if we only had one maker of insulin or epinephrine. One factory fire and people die. So yes, prices are weird. But at least we’re not back to 2021 when pharmacies ran out of everything. Maybe the real win isn’t lower prices-it’s just not dying because of a supply glitch. Keep pushing for more makers. The rest will follow.